Ever since Mario Draghi's damning report on European growth, EU leaders have promised reform. Better yet, they have promised committees, and possibly even summits. But while most Europeans agree on Draghi’s verdict, nobody knows how exactly we Make Europe Great Again, and whether it means more EU (Macron liberalism), or less EU (AfD illiberalism).

This is not the first time European nations have had to face their “growth” problem. After the 1973 oil crisis (and the resulting economic slowdown), France overhauled its entire energy infrastructure with a 1974 plan to double down on nuclear. In the decade following the crisis, nuclear energy accounted for up to 80% of its electricity1. France became the second country to implement high speed rail, built and operated the supersonic Concorde, created and launched the Ariane space program, founded AirBus and the A300s, as well as massive infrastructure projects domestically and across Africa.

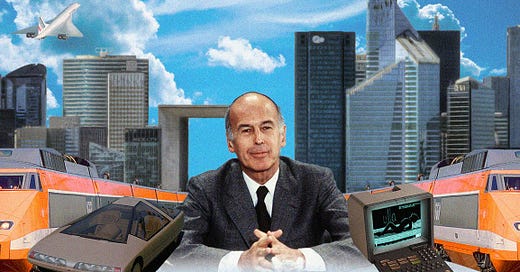

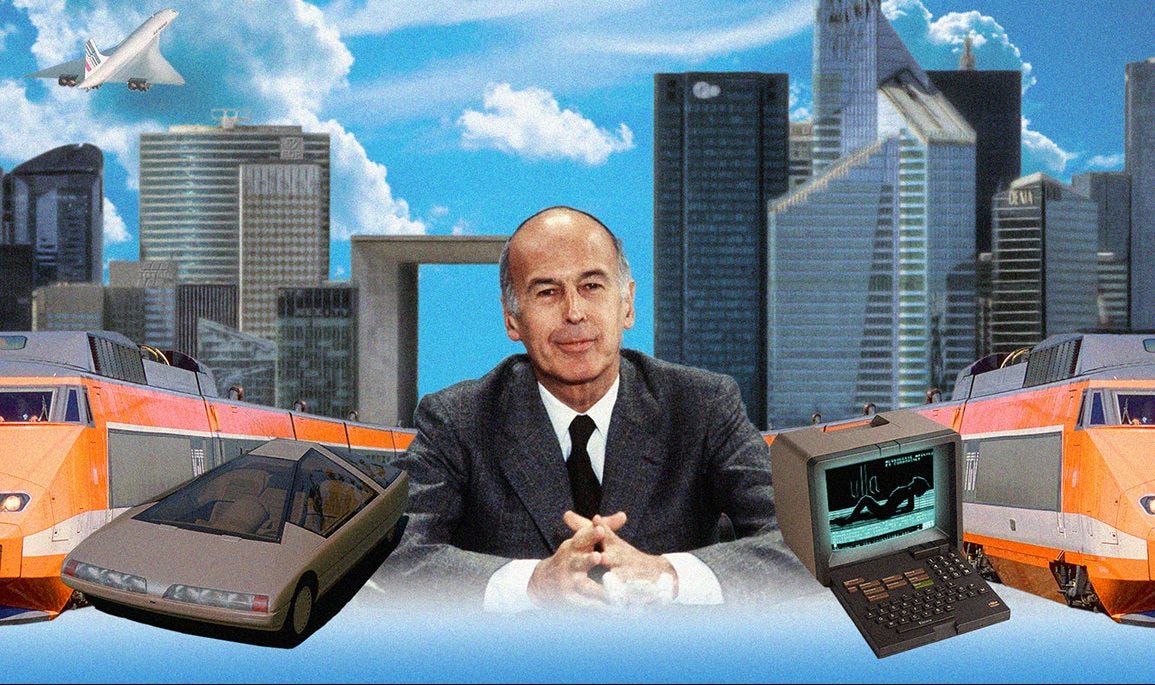

These projects, overseen by president Valery Giscard d’Estaing, embodied European modernism, with growth that revolved around investments and subsidies, rather than regulation and taxes.

Giscard implored future generations to have “specific targets…with the will to reach them”, pleading for definite optimism, and building tangible infrastructure to enable that vision.

That advice is now being picked up by a community called the Giscardpunk, a parallel universe imagined by Giscard’s most ardent supporters. In this fictional timeline, Valery Giscard d’Estaing not only won his 1981 re-election against Francois Mitterand (the socialist leader of welfare reform) but also steered Europe into a pro-tech utopia.

The 1981 election is an interesting turning point, not just for France, which pivoted from Giscard’s trailblazing technology juggernaut to Mitterand’s socialist nanny state, but for the European continent as a whole. Ambitious and large scale infrastructure projects became increasingly rare throughout the 80s and 90s, making way for expensive welfare programs, the demographics of which are no longer sustainable.2

Infrastructure investment and modernization were a definite optimist vision of the future, providing a direct rebuttal to the EU’s current indefinite approach on technology.

After creating the most restrictive regulatory environment in the world, EU leaders announced an AI sovereign wealth fund in February to throw €200 billion at the innovation problem. While von der Leyen has said that European AI should focus on applications within industry, she hasn’t specified what industries this means, or why. European leaders leave it up to the now crippled European entrepreneurs to figure out innovation, with no guidance and no plan.

Imagine for a moment that Europe won the AI arms race. What would that even look like? Is it open-source? State sponsored? Joint ventures? If it looks like a watered down version of Silicon Valley with “European values” sprinkled on top, or worse if it looks like a censorious Chinese spy-state, it will mean European leaders failed to provide a concrete vision for their own future.

Today, the saudis are discovering their inner-Giscard and laying out visions for the future with projects like NEOM, which outlines the next 100 years of Saudi infrastructure, urbanism, and technology. We’re happy to ridicule NEOM here in Europe, and it certainly has its problems, but despite delays and controversies the Saudis have achieved something which the European mind cannot comprehend: creating a clear, ambitious, definite vision. Without initiative or a clear direction for progress, Europe continues to fossilize into a cultural theme park for Americans and Chinese tourists, as any large infrastructure atop its decrepit paved roads are deemed heretical by NIMBYs.

Modern European NIMBYism, à la Thierry Breton, encompasses technology and innovation too, a kind of “let them build the tech elsewhere, and we will regulate it here”. But there are only two ways to get this much say over the products and services available in your country. The first option is to close off your citizens to the outside world, and create a great censorship firewall, which the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act are currently doing. The second option is to build compelling alternatives locally, which you control and influence more easily. This second option, and current EU strategy of regulation without innovation, relied on a US administration that was complicit in the fleecing of its own companies like Google and Meta. Now that the faucet has been turned off, and US companies are protected by the Trump administration, Europe has no choice but to once again invest in its own alternatives and infrastructure, and hope to recapture its 1970s spirit of acceleration.

As for Giscardpunk, it's not clear what real effect his re-election would have had on modern Europe, and whether that acceleration and progress could have continued. The 1971 Great Stagnation was already underway in the United States, and like most trends was slowly making its way to Europe, Giscard or no Giscard. But the slowdown in productivity and technological innovation has only worsened over time. Rather than merely slowing down progress, Europe actually regressed on many fronts and its productivity growth sits at just 0.7% as it now only spends half of what the US does on R&D.

France in general is no longer in a position to act alone for radical modernization. It's simply too crippled with debt, too polarized, and too entrenched in the benefits it now owes to its aging population. Every dollar of public funding is more and more contested across ever more separated extremes of its political aisle. In the end, the money goes into a nebulous bureaucracy, maintaining a dying welfare state just a little bit longer, with no tangible infrastructure or growth to show for. Giscardpunk today would require a long period of austerity to provide a similar debt-free, low-tax environment to 1974, which makes it ring more like delusional French chauvinism than a real economic vision3. For better or for worse, Europe's recent urge to accelerate is one of France's only opportunities to exit its crisis.

Deep down, we all know that Europe is more likely to regulate any new opportunities into the ground, than ride its economic upside all the way out of crisis. Still, Giscardpunk is an important reminder that Europe can modernize and innovate its way out of economic crisis. It’s been done before, and it could be done again. But while the demographic and economic fundamentals have changed, the first step remains a definite vision for the future.

Since then, French nuclear has devolved into the disaster we know today, as the country now struggles to build 1 reactor in the same amount of time it took to build most of its nuclear reactor fleet.

In Giscard’s time, 4 workers paid for 1 retiree and a third of the population was under the age of 20. Nowadays, 1.6 workers pay for 1 retiree and 25% of the population is retired. With minimal productivity gains, the math of the French welfare state no longer works. - source

Giscardpunk is mostly satire, but also a somewhat interesting starting point to analyze current European problems.