I Can't Believe It's Not Progress!

Growth through globalization is not real progress

The future does not look like The Future. For children of the 1960s, The Jetsons was the embodiment of American Optimism.

But for those of us born a little later, the show instead reminds us of past technological aspirations from a previous American golden age.

The Jetsons was premised on a simple (albeit naïve) assumption that the 1960s rate of innovation would continue more or less forever, and with it came flying cars, jet packs, housekeeping robots and energy too cheap to meter, to not speak of the anti-gravity devices and food synthesizers. But what was harder to predict was that the next half-century of what we call progress would be achieved by way of globalization rather than innovation, as cheap labor from abroad filled the vacuum left behind by a lack of technical progress in fields like robotics, agriculture or manufacturing.

Despite a steady growth in wealth and quality of life since the 1960s, those who grew up consuming sci-fi may be disappointed by the aesthetics of progress and the un-sci-fi-ness of it all. Sure, people are wealthier than before. And quality of life is better than before, yet the 21st century envisioned by The Jetsons’s writers, looks more like their own 1962, than their character’s 2062 setting.

This cognitive dissonance lies in the difference between the terms growth and progress. Despite growth and progress being historically correlated, their trends have bifurcated since the 1970s. While growth can come from a rising population and increased consumption (nowadays sustained by foreign labor), true progress as envisioned by the show hinges on transformative innovation that expands what’s possible for all.

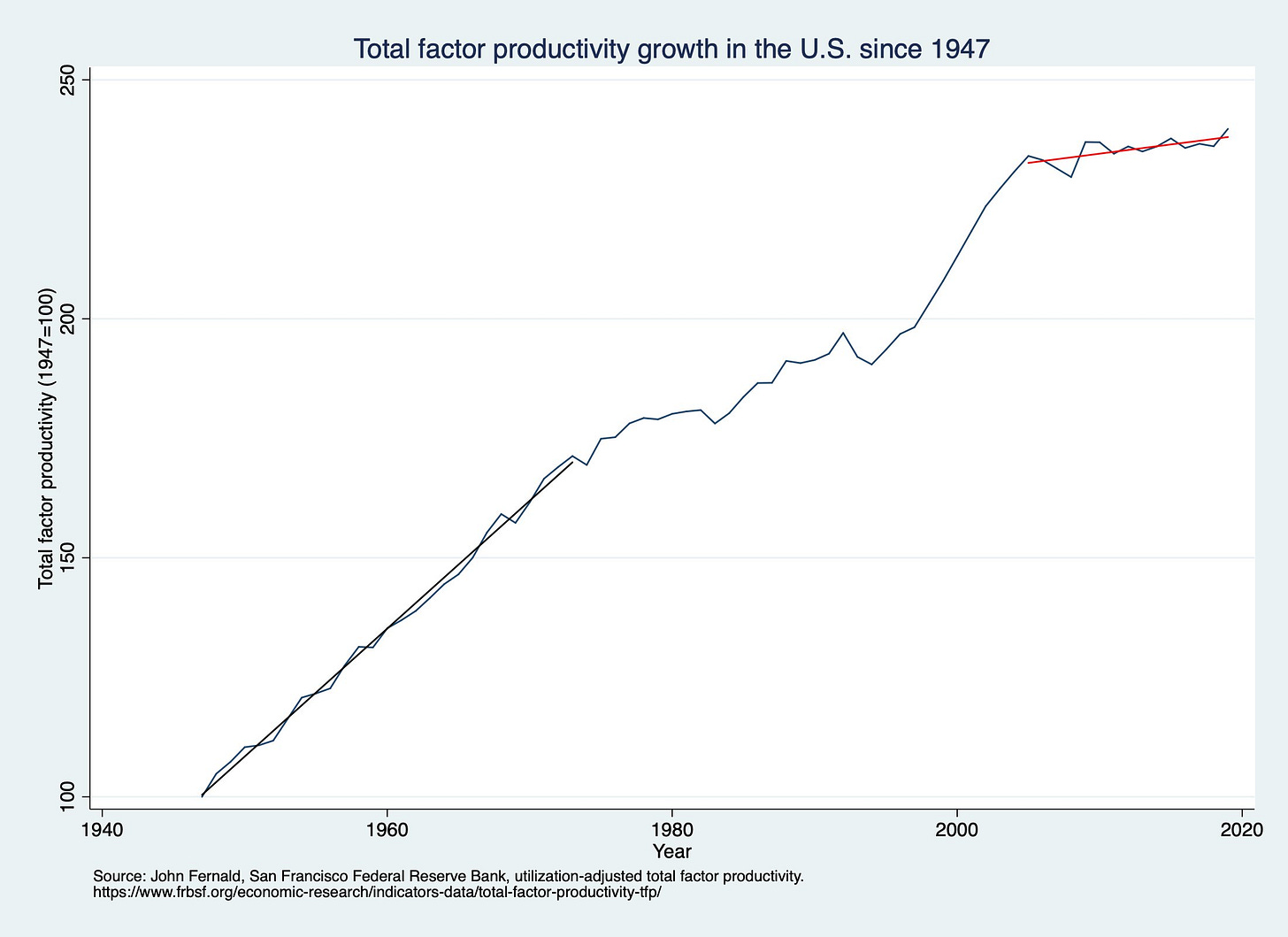

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) helps us get a clearer picture of this difference between growth and progress. Growth and the resulting wealth can often be measured in GDP per capita, while TFP measures the portion of economic growth not explained by increases in labor and capital, reflecting instead improvements in efficiency from technology, innovation, or R&D.

TFP is most similar to that rate of innovation The Jetsons assumed would remain constant. Instead, it has fallen from a yearly ~2% from 1930-1970s, to less than 1% in the half century since.

While progress through globalization and progress through innovation might seem like progress all the same, there is a qualitative difference between their outcomes. A prime illustration of this is Jane Jetson — the 1960s housewife of tomorrow, and her robot maid Rosey, which enables emancipation from household chores. As with the washing machine and other automated home appliances of the 1960s, this automation, it was hoped, would bring about a new wave of improvements in quality of life for women previously burdened with homemaking.

Ultimately, the quality of life improvements and automated lifestyles weren’t afforded by inventions like Rosey the robot, which we are still decades away from building. Instead, the social change allowing Western women to fill new executive and C-suite roles was largely enabled by a global workforce of babysitters, cooks, nannies and maids who automated their home lives and delivered a semblance of Jane Jetson’s quality of life.

It turns out you can mass-produce technology, but you can’t mass-produce a living wage above the poverty line. Once the cost of labor hits that floor, you’re fresh out of “progress” to offer the lower classes of society.1

Instead of achieving automation through technology, we’ve emulated the same outcomes of progress through globalization, and in turn created a new kind of fake progress. It looks, smells and tastes like progress, but under the hood lie hidden costs and benefits unequally distributed.2

An important outcome of fake progress, and the slower rate of innovation, is a future that looks more and more like the present. Since 2007, non-farm TFP has fallen to an average of just 0.5%. While the previous 2% annual rate of progress implies a doubling of productivity every 35 years, a rate of 0.5% achieves this every 139 years.

As we approach the fictional 2062 setting of The Jetsons, each passing year is a reminder of how far we still are from its flying cars, robot labor, and abundance. Half a century after The Jetsons first aired, the world that seemed a few generations away now seems a few centuries away, and the future is only getting further and further.

This fake flavor of progress, which gives us growth without innovation, misleads us as we continue to grow our economy and quality of life. The Jetsons reminds us to instead strive for real progress, which has the potential to create virtuous cycles of growth by leveraging technology’s compounding effects, ensuring more equitable outcomes for all.

- Tom J. Pandolfi

This cheap and sometimes illegal labor creates a difficult dilemma for politicians, between accepting that the minimum wage is too high to adequately maintain the jobs needed in the economy or accepting that working conditions offered to illegals are unacceptable for ordinary citizens. It’s a dilemma which can only be transcended by automation.

Real progress is the kind afforded by innovation and capitalism, wherein technology improves in a competitive market and costs go down for consumers, allowing it to become increasingly accessible and affordable across society.